Writing a Solo Adventure

July 23, 2018

I enjoy writing and playing solo game adventures (or "interactive novels," as the book trade calls them). A solo is sort of a cross between a novel and a computer program. It's a fictional adventure in which you, the reader, take the part of the hero. Your decisions control the course of the adventure. Most solos written for game fans also contain "game mechanics" and rules for character creation, allowing a greater variety of adventures from the same book.

The first solo adventures, as far as I know, were published by Flying Buffalo for their Tunnels & Trolls game. My own introduction to solo writing came with Death Test, a Fantasy Trip adventure written in 1978. (Collected with Death Test 2 in this box set.)

Interactive fiction has come a long way since then. An average T&T or TFT adventure would have less than 200 entries (Death Test had 167) and required relatively complex game mechanics. Modern interactives, like the Car Wars gamebooks or the hugely successful Fighting Fantasy series, have very simple rules, short enough that they can be included in each book.

Where will interactive fiction go next? Good question. The genre seems here to stay. Solo adventures won't replace books – or regular games, for that matter – but they present an amusing change of pace from "heavier" pastimes. And they're a great introduction to gaming.

Would you like to write a solo? It's not easy – but there aren't any big secrets, and I'm about to reveal the little ones. The thing to remember about a solo is: keep plugging; keep writing, keep checking. Essentially, when you write a solo, you are writing a computer program . . . in English instead of a computer language. If you leave a possibility unaccounted for, or a number refers to the wrong paragraph . . . well, you've got a problem. And so do your readers.

Don't Start Yet!

Before you write a word, there are several things you really ought to have:

(a) Familiarity with the game system you're going to use. Don't try to write a Fighting Fantasy unless you've played several of their books already; don't try to write a Car Wars until you've been through all the ones now published. Of course, if you want to create a system from scratch, you can – but that will make your job harder if you are trying to get it published professionally.

(b) Friends to playtest the game. As you will see, this is a must.

(c) A computer with good word-processing software, and a fast, clean printer. This is not a must; you can get along with a typewriter. People (including me) were writing solos for years before home computers became popular. But . . . writing a solo requires at least two drafts, and generally three. it requires massive rearrangement of paragraphs within the document. It requires accurate renumbering of the paragraphs after you rearrange them. And it may require you to copy paragraphs from one section to another, to avoid massive retyping.

All these things can be done without a computer. But take it from me . . . they are much, much easier with a computer.

(d) Patience . . .

Initial Outlines

The first step in creating a solo adventure is the outline – just as though you were writing an ordinary book. This outline gives the main plot line, which your hero will follow if he is successful. It also defines the length. A book-length interactive will have 200 to 400 paragraphs, depending on complexity (and how much descriptive material you shovel into the paragraphs between decision points). An adventure written for magazine publication can be as short as 75 to 150 paragraphs without being trivial.

Now make notes about subsidiary plotlines – other "paths" your hero can take. Some writers use the One True Path system, where any false decision can injure or doom the hero. Others prefer to have several possible paths to success. Personally, I prefer the latter system; my Scorpion Swamp, part of the Fighting Fantasy series, includes an early choice-point that affects the whole rest of the adventure – but any of the three choices you make there can be "right."

Now you have an outline with branches – some ending in literal dead ends, others looping back to join the main trunk. Break this outline into encounters. A 400-entry adventure will have between 20 and 30 encounters. You need at least 20, and a good idea of their order, before you start to write. Note that, in an average play session, only perhaps 15 of these encounters will take place.

Next you should draft the introduction and the conclusion. The introduction will be paragraph 1 in the final version. (If there is to be a separate introduction, you will, in effect, split off the last part of the introduction and let it be paragraph #1.) If there is a single best ending, plan in advance for that to be the last numbered paragraph. Otherwise, don't worry about it.

Now you're ready to begin writing. Assign each encounter an number – the first encounter is #1, and so on. Each paragraph within the encounter has a letter. The first one is 1A; the second one is 1B, and so on. If an encounter has more than 26 entries, go to 1AA, and so on. But any encounter that long should quite possibly be broken into two encounters.

When I write, I give each encounter a simple heading, such as:

6. Everyone is Eaten by Newts – 9 entries

This lets you create a table of contents and keep track of the number of entries you have written. The "9" at the far right represents the current number of entries in the encounter; you'll update this as necessary.

Playtest

When most or all of the entries are written, it is time for the first stage of playtesting. Don't try to do this all by yourself. You know what is supposed to happen, so you'll miss errors that would be obvious to others. You shouldn't have to twist your friends' arms very hard to get them to play your adventure. (If you have a problem here, your solo may be boring, which is an entirely different problem.) If you're writing professionally, this is the stage at which your editor will want to get a look at the draft, too.

Keep playtesting until the adventure is fun and makes sense, and all errors seem to be out.

Somewhere in here, you'll want to draw up a flowchart, showing which paragraphs lead where, and why. This takes time, but it's a valuable tool. It can graphically show you such problems as:

Isolated paragraphs that you can't reach from the rest of the adventure, because a reference was omitted;

Dead ends that don't go anywhere;

Loops that allow the player to read the same paragraph over and over again (some loops are intentional, but accidental ones can cause problems).

Renumbering

When your playtesters are happy with the adventure, it's time to renumber – changing the alphanumeric paragraph designations to straight numbers. The first step in renumbering is to prepare two sheets. One is just a list of numbers from 1 to 400 (or whatever). The other one is a list of all the alphanumeric paragraph numbers in your final draft. When you assign new numbers, you will note the new number on each sheet, to aid in double-checking. For instance, if you decide that 3F is to be 211, you write "3F" beside #211 on the number sheet, and "211" beside #3F on the alphanumeric sheet. This can save a lot of effort later when you are tracking down errors.

Start by recording any paragraphs with pre-assigned numbers. This will include the first and last paragraphs. It will also include any paragraphs that have had their numbers preassigned as clues – e.g., "To call Cthulhu, add the digits of the phone number together and go to that paragraph."

The next step is only important if you're writing for publication. Artwork! You don't have to draw the pictures, but you can help decide what should be illustrated. Choose all the paragraphs that need full-page art and assign their numbers. Spread them evenly throughout the book. Thus, it there are 20 illustrations for a 400-paragraph adventure, the first should be around #20, the second 40, and so on. This does not account for any illustration specifically designed for the introduction or conclusion. Those will be, respectively, before the first page and after the last page.

Now renumber the remaining paragraphs. Start with the first encounter. Suppose it has 15 paragraphs left (allowing for any that have already been assigned). 400 divided by 15 is about 27. So this encounter gets to use #27, #57, and so on.

However, it is better not to just take the paragraphs in order. That is, do NOT make 1A #27, 1B #54, and so on. Instead, go down to the middle of the encounter and assign 1G to #27; then skip down to the end and assign 1N to #57, then go back to the beginning and assign 1B to #81 - and so on. This makes the book less predictable.

If the number you need has already been taken, just skip forward or back until you come to one that has not been taken. No big problem. The formula is intended to achieve wide spacing between conected paragraphs, not to insure arcane mathematical perfection.

Now double-check the two number lists against each other, to make sure they both agree and no numbers have been used twice or left over.

When the lists finally agree, go back to the text and renumber the paragraphs. This can be done by hand if necessary. Or you can mark all corrections on a printout and then go through and make them. But some word-processing programs will let you write a "key procedure" to do a long series of search-and-replace functions. Writing the key procedure will be time-consuming, but when you are through, you can go away and let the computer do the work.

When you are through, you will have a lot of numbered paragraphs, out of order. Put them in order. If you have a computer, just settle down to a few hours of Block Move commands. Otherwise, you probably have to retype the whole manuscript.

Read through and make sure that you have no missing or duplicate numbers. If you find problems, track them down and correct them. Your earlier drafts and sheets of replacement numbers will be helpful here.

Now print out the renumbered version and playtest again. Try to get some new playtesters. In addition to other sorts of errors, you are looking for the inevitable places where connecting paragraphs from different encounters will have come too close together. When such a bad connection is found, change the number on one of the paragraphs to move it far away. Do this by switching with another number. Care is needed here, so you don't create more problems than you solve.

Now you're through. The adventure is ready for typesetting and layout (if you are doing it professionally) or to boggle your friends' minds (if you've done it for yourself). But if you've taken it this far and you don't have a publisher, write us for a release form. We just might be interested...

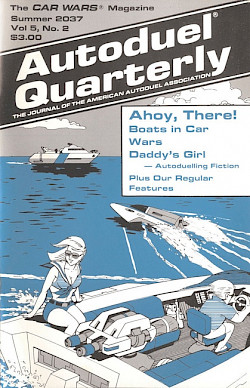

NOTE: This article was first published in 1987 in Autoduel Quarterly 5/2.